Editor’s note: This piece was originally published at Health Affairs Blog on February 26, 2018.

In 2015, Congress passed the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) on a strong bipartisan vote. In addition to repealing the Sustainable Growth Rate formula that was used to set the level of physician payment rates, MACRA changed the structure of Medicare physician payment in ways intended to encourage clinicians to deliver more efficient, higher-quality care.

MACRA envisioned a long-run transition away from fee-for-service payment toward so-called advanced alternative payment models (APMs), models in which providers bear financial risk for the overall cost and quality of the care they deliver, driven in part by bonuses MACRA created for participation in such models. In the near term, however, most clinicians will participate in MACRA’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), a value-based purchasing program that adjusts clinicians’ fee-for-service payments upward or downward based on their cost and quality performance, as well as their completion of certain activities related to electronic health records (EHRs) and “practice improvement.”

While the first performance year of the MIPS program has just ended, some observers, including the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, have already raised concerns that MIPS will fail to improve patient care, even as it generates substantial administrative burdens. In this blog post, we argue that these concerns are well founded and that MIPS or a similar value-based purchasing program is unlikely ever to achieve its goals. This reflects both specific problems with how MIPS measures performance and broader challenges with assessing performance at the level of an individual practice when patient care involves many different providers and practice-level sample sizes are often small. We argue that Congress should repeal MIPS, replacing it with stronger incentives to participate in advanced APMs and targeted incentives for certain well-defined activities currently encouraged under MIPS.

Overview Of Medicare Physician Payment Under MACRA

MACRA envisioned linking payment to performance for all Medicare clinicians either through MIPS or through participation in an advanced APM. Clinicians are permitted to choose between the two tracks, each of which is briefly described below.

Track 1: Merit-Based Incentive Payment System

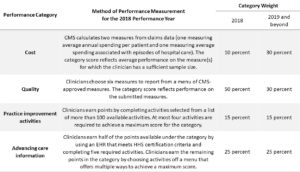

MIPS measures clinicians’ performance in four categories: cost, quality, practice improvement (which concerns practices’ completion of various activities intended to improve patient care), and advancing care information (which concerns practices’ completion of various activities related to use of EHRs). Performance in the cost category is evaluated using measures specified by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) that are computed using information submitted on claims. By contrast, for the quality and practice improvement categories, clinicians are offered a menu of eligible measures and activities, and clinicians’ scores are then based on the measures or activities for which they elect to report information to CMS. The advancing care information category also offers clinicians considerable choice, although the category also includes several relatively simple required activities. Exhibit 1 provides additional detail on how MIPS measures performance in each of the four categories for the 2018 performance year.

CMS uses the information submitted for each of the four categories to calculate a “composite performance score” for each clinician and calendar year that can range from 0 percent to 100 percent. Exhibit 1 reports the percentage of the overall composite score contributed by each category. That composite score is then translated into an upward or downward adjustment to the clinician’s fee-for-service payment rates for services delivered two years after the performance year. MACRA also requires CMS to publish the composite score and other MIPS data through its Physician Compare initiative starting in 2018.

MIPS replaced three older value-based purchasing programs operating under the Medicare physician fee schedule: the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), which provided financial incentives for physicians to report quality measures; the Value Modifier, which adjusted physician payments upward and downward based on their performance on measures of cost and quality; and the Electronic Health Record Incentive Program created by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, more commonly known as the “meaningful use” program. One commonly cited objective of consolidating these three programs was to reduce administrative burdens for clinicians, but, as discussed below, there is little reason to believe that this objective has been achieved in practice.

Track 2: Participation In Advanced Alternative Payment Models

Clinicians are exempt from MIPS if they deliver a sufficient fraction of their care through an advanced APM, defined as a payment model that requires providers to bear significant financial risk for cost and quality performance, report clinical quality measures, and use EHRs. The most prominent advanced APMs in Medicare are the various “two-sided” accountable care organization (ACO) models that operate through the Medicare Shared Savings Program and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Some “medical home” models that involve more limited financial risk, such as CMS’s Comprehensive Primary Care Plus model, also qualify as advanced APMs.

Clinicians that qualify for this track earn a bonus payment equal to 5 percent of their physician fee schedule revenue, in addition to any incentive payments associated with the advanced APM itself. These bonus payments are available for participation in an advanced APM from 2017 through 2022. In later years, the bonus payment disappears, but the Medicare physician fee schedule rates applicable to advanced APM participants will rise 0.5 percentage points per year faster than those applicable to nonparticipants, which will gradually recreate an incentive for advanced APM participation.

MIPS Is Unlikely To Meaningfully Improve Patient Care

MIPS aims to improve the quality and efficiency of patient care in two main ways. First, by adjusting clinicians’ payments based on the cost and quality of the care they deliver, MIPS aims to create direct financial incentives for clinicians to improve on those dimensions. Second, public reporting of information collected under MIPS could, in principle, help patients choose a clinician and create competitive incentives for clinicians to improve their performance. Unfortunately, none of the four MIPS performance categories is constructed in a way likely to create the desired incentives.

Three of the four MIPS performance categories—quality, advancing care information, and practice improvement activities—are undermined by clinicians’ ability to choose the measures and activities they are evaluated on. The amount of choice is substantial. In the quality category, clinicians must report only six measures, but the median specialty among the 15 largest specialties will have 23 measures to choose from. For the practice improvement category, clinicians can achieve a maximum score by completing at most four activities from a list of more than 100 available activities. The advancing care information category does not allow completely free choice, but the required activities are relatively simple to complete and clinicians have many paths to achieve a maximum category score.

MIPS’s designers allowed this degree of clinician choice because different types of clinicians provide different tests, procedures, and therapies, which necessitates using different measures to assess their performance. Unfortunately, while allowing clinician choice is a superficially appealing way of customizing MIPS to each clinician’s practice, it seriously undermines MIPS’s effectiveness. Most obviously, allowing broad clinician choice means that each individual clinician will end up reporting different measures, directly undermining MIPS’s ability to help patients compare clinicians.

Allowing broad choice of measures also undermines the effectiveness of MIPS’s direct financial incentives. Because of this flexibility, clinicians will often be able to select quality measures for which they are already attaining a very high score. Similarly, clinicians will frequently be able to achieve the maximum score under the practice improvement and advancing care information categories purely by reporting on activities they were planning to undertake anyway. Clinicians’ ability to achieve the maximum score (or a very high score) by merely focusing on “easy” measures and activities will greatly diminish the incentives to improve patient care that MIPS would otherwise have created. An additional problem is that the measures and activities where it is easiest for a particular clinician to achieve a high score will generally not be the measures and activities where additional effort would pay the greatest dividends for Medicare beneficiaries and the Medicare program. This risk is magnified by the fact that each of these three performance categories includes measures that are not obvious priorities for quality improvement efforts.

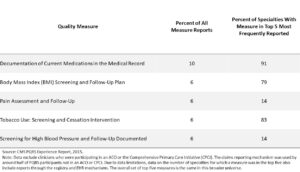

Experience under PQRS—a predecessor program to MIPS that paid clinicians to report on quality measures but did not link payment to performance on these measures—demonstrates that clustering around “easy” measures is a real concern. Exhibit 2 reports the top five most frequently reported measures among clinicians reporting to PQRS in 2015 via the claims mechanism, the reporting mechanism most commonly used by clinicians not participating in ACOs. Each of these measures pertains to routine components of medical practice that should be relatively easy to complete. These five measures accounted for more than one-third of all measure reports through the claims mechanism and were among the top measures reported across a broad array of specialties.

Constructing Clinician-Level Cost Measures For MIPS’s Cost Category Poses Technical Challenges

MIPS’s cost category is better than the other three MIPS categories since both cost measures currently in use are coherent and relevant, and clinicians are not permitted to choose how they are evaluated. For these reasons, this category may generate some benefits, even if only by raising clinicians’ awareness of their effect on total system costs.

However, the cost category also has important shortcomings. The most fundamental problem is that many practices participating in MIPS are relatively small, so cost performance must be measured based on data for modest numbers of patients. As a result, chance plays a significant role in determining whether a clinician receives a high or low score for this category. This dilutes clinicians’ incentives to invest in improving efficiency.

A second problem stems from the need to measure cost performance at the clinician level for all clinicians participating in the Medicare program. CMS is currently handling this problem by creating multiple different cost measures, scoring clinicians on all the measures for which minimum sample size requirements are met, and then averaging performance across the measures. Unfortunately, this approach creates a haphazard overall set of incentives to improve efficiency. This problem will become much more severe if CMS follows through on its stated intention to increase the number of cost measures in use in MIPS.

MIPS’s Existence May Discourage Participation In Advanced APMs

MIPS’s existence may also have the unintended effect of discouraging some providers from participating in advanced APMs, which, as discussed in the next section, have the potential to meaningfully improve patient care. In particular, clinicians who elect to participate in advanced APMs receive a bonus payment equal to 5 percent of their physician fee schedule revenue but must forgo any payment adjustment under MIPS. Clinicians who are plausible candidates for advanced APM participation are likely to be well positioned to obtain positive MIPS adjustments, at least on average, so MIPS’s existence will tend to make advanced APM participation less attractive.

This disincentive for advanced APM participation is likely to be relatively limited in the near term—CMS estimates imply that the average positive adjustment under MIPS will be only 1 percent for the 2018 performance year—but is likely to become larger in future years. In addition, provider confusion could magnify this disincentive. While positive adjustments under MIPS will be small in practice, positive adjustments as large as 25 percent are theoretically possible for 2018 performance year. Clinicians who erroneously expect large positive adjustments would be likely to opt for MIPS over an advanced APM.

Congress Should Eliminate MIPS And Expand And Improve Incentives For Advanced APM Participation

For the reasons described above, MIPS is unlikely to meaningfully improve the quality or efficiency of patient care. At the same time, MIPS will impose significant administrative burdens on both providers and the federal government. Notably, CMS estimates that providers will spend $694 million complying with MIPS reporting requirements for the 2018 performance year. External estimates of the administrative costs of prior quality reporting programs suggest that burdens could be even larger.

This unfavorable cost-benefit profile justifies major changes to MIPS, and we would discourage Congress from merely tinkering around the edges. MIPS’s design surely could be improved; however, many of MIPS’s shortcomings are likely unavoidable in a system that seeks to measure overall quality and cost performance at the level of each individual clinician or practice and then adjust fee-for-service payment rates on that basis. And, indeed, empirical research on prior value-based purchasing programs that take this basic approach has found little evidence that they improve patient care (Note 1).

Instead of seeking to improve MIPS, we recommend that Congress eliminate MIPS and put two types of policies in its place. First, we recommend that Congress expand and improve MACRA’s incentives for participation in advanced APMs. Evidence to date implies that APMs can be effective in improving both the quality and efficiency of care. While the magnitude of the measured benefits of APMs has been modest, there is some reason to believe that effects will grow over time and that diffusion of these models may generate systemic benefits not captured in existing research. Second, for providers not yet participating in advanced APMs, we recommend that Congress create targeted incentives for certain well-defined activities that can be readily measured and rewarded at the clinician level.

Recommendation #1: Expand And Improve Incentives For Participation In Advanced APMs

To accelerate the transition to advanced APMs envisioned by MACRA, we recommend that Congress expand and improve MACRA’s incentives for participation in such models:

- Increase the incentive for advanced APM participation: Congress should consider increasing MACRA’s incentive for participation in advanced APMs through a budget-neutral combination of additional bonuses for participants and penalties for nonparticipants. The appropriate magnitude of these incentives merits additional research, but we believe that meaningful increases relative to current law are warranted. A larger incentive for advanced APM participation would have two types of benefits. First, it would directly increase advanced APM participation, with attendant benefits for patient care. Second, it would enable CMS to deploy versions of APMs that create stronger incentives to improve quality and efficiency. Inevitably, some APM design decisions that strengthen incentives to improve care (for example, increasing the amount of financial risk providers must bear or setting cost “benchmarks” based on regional average costs instead of a provider’s own historical costs) also make APM participation less attractive for some providers, particularly low-performing providers. The fear that many such providers would opt out of APM participation has often constrained CMS’s APM design choices. A larger incentive for advanced APM participation would relax this constraint by making advanced APM participation more attractive.

- Create advanced APM participation incentives for new categories of providers: Congress should extend incentives for advanced APM participation beyond physicians to other categories of providers, particularly hospitals. We recommend that this incentive be structured as a budget-neutral combination of bonuses for participants and penalties for nonparticipants.This change would reinforce the beneficial effects of increasing advanced APM participation incentives for clinicians. In addition, extending these incentives to other types of providers would give these providers a greater stake in the deployment and success of advanced APMs, which may be necessary to fully realize these models’ potential to improve patient care.

- Make the advanced APM bonus permanent: MACRA’s bonus for advanced APM participation expires after the 2022 performance year, and the 0.5 percent higher annual payment rate update MACRA provides for advanced APM participants after 2022 will take a full decade to replace it (before potentially creating excessive incentives for advanced APM participation in the very long run). This design could undermine providers’ willingness to make long-term investments in advanced APMs. Congress should facilitate long-term planning by creating a constant, permanent incentive for advanced APM participation in 2023 and subsequent years that is at least as strong as the incentive from 2017 through 2022 and discarding the higher payment rate updates for advanced APM participants.

- Smooth out the “cliff” in the eligibility criteria for the advanced APM bonus: Currently, clinicians must have a specified share of their patients or revenues associated with advanced APMs to receive the advanced APM bonus. This creates a “cliff” in which a small change in a provider’s circumstances can lead to a complete cutoff of bonus payments, and it creates no incentive to increase the extent of a providers’ participation in advanced APMs once the threshold level is reached. Congress could smooth this cliff by phasing the bonus in gradually above some level or adopting a tiered payment structure.

Recommendation #2: Create Targeted Incentives For Certain Clearly Defined, High-Value Activities

While we view advanced APMs as the most promising long-term strategy for linking payment to performance in Medicare, it will likely be some time before all providers are participating in advanced APMs, even if Congress expands incentives for advanced APM participation as we recommend above. We therefore recommend that Congress create small payment incentives targeted at certain well-defined activities (via a budget-neutral combination of bonuses and penalties) for clinicians not participating in advanced APMs:

- Use of a certified EHR: To help anchor common national standards for EHRs that promote interoperability, Congress should create a small payment incentive (approximately 0.5–1 percent of payments) to use an advanced EHR that meets the latest EHR certification standards issued by the Department of Health and Human Services. Practices could earn the incentive merely by showing that they have a suitable system installed and in active use, similar to the requirements currently in place for advanced APMs. Clinicians would not be required to perform any specific activities with that EHR, unlike under the MIPS advancing care information category.

- Reporting to clinical data registries: Clinician reporting to clinical data registries can generate benefits for the health care system as a whole by creating a knowledge base that can be used to identify strategies to improve patient care and that allows clinicians to compare themselves to their peers. Congress should therefore create a small payment incentive (also approximately 0.5–1 percent of payments) for clinicians or practices to report to registries that meet rigorous criteria. Congress should consider also applying this incentive to clinicians participating in advanced APMs, as the systemic benefits of registry reporting exist in that setting as well.

In the absence of direct payment incentives for clinicians to improve the quality and efficiency of care, there may also be a rationale for financially encouraging clinicians to undertake rigorous practice improvement activities. However, to avoid the shortcomings of MIPS’s practice improvement category, policy makers would need to find ways to both identify improvement activities that actually create significant value for patients and the Medicare program and limit practices’ ability to claim credit for activities they would have performed anyway. This may or may not be possible in practice, but exploring potential approaches would be worthwhile.

Conclusion

There is broad agreement that the quality and efficiency of the care received by Medicare beneficiaries can and should be improved. Unfortunately, MIPS is unlikely to achieve that objective, despite creating substantial administrative burden. We therefore recommend that Congress discard MIPS in favor of an alternative approach that builds on MACRA’s incentives for advanced APM participation. We recognize that Congress may be tempted to wait for several years of experience under MIPS before considering major changes like these, but that would be a mistake. Forging agreement on a system to succeed MIPS will take time and effort. That work should begin as soon as possible.

Note 1

Value-based purchasing programs that target a single outcome or a small set of outcomes, such as the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, have met with greater success. However, the success of these types of more targeted programs is of limited relevance to MIPS, which seeks to improve care in a comprehensive way.

Authors’ Note

Tim Gronniger is a senior vice president at Caravan Health, which helps providers set up accountable care organizations. The overwhelming majority of his work on this piece occurred before Gronniger began working at Caravan, while he was a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution.

You must be logged in to post a comment.